And why you should

Leon Purton Jun 12

Homer—the Ancient Greek poet Homer—created a character, a friend of Odysseus and adviser to Telemachus, called Mentor. Mentor was Telemachus’ sage counsel, but in a late twist in the story, it was discovered that Mentor was in fact the Goddess Athena in disguise.

If it takes a goddess to pretend to be a man to teach someone, it’s no wonder you feel overwhelmed the first time someone asks you to be their mentor.

What exactly is the role of a mentor? Am I qualified? What would make me qualified? What can I help them with? I’m still working it out for myself! In my time in the military I have had several informal and formal mentors, and as I’ve developed I have become an active formal and informal mentor myself.

I’ve found that, to do it properly, you have to create the right environment for the relationship.

“People really don’t care how much you know, till they know how much you care.“— Roosevelt

A mentoring relationship is one of the most important things you can create in your career or life. Seeking them out may boost your career progression. But more importantly, becoming one will provide for your own growth and development. Being a mentor is rewarding in so many ways, and you’ll nearly always get out of it more than you give.

To assist you in your journey, I’ll give you three simple but important steps to build a fantastic mentoring relationship.

Step 1: Boundaries

When I start a mentoring relationship, the very first thing I want both of us to be clear about is what our expectations are. What are we open to discussing, and perhaps more importantly, what are we not?

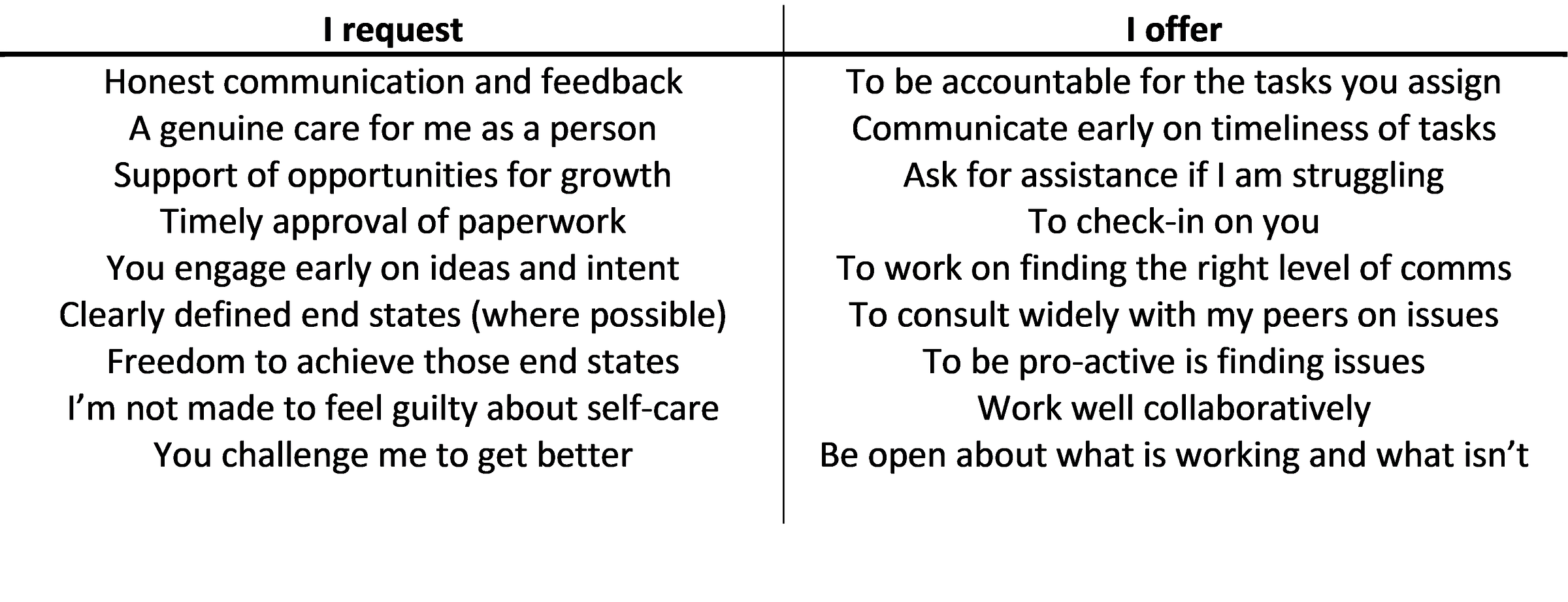

I have found that often people come to a mentor assuming that they will just know what they really want from the relationship. Or, alternatively, they will come to you with one problem that they feel comfortable talking about, and depending on how you do with that problem, they will then broach the one they really want help with. Sometimes they won’t actually understand the areas they need to be challenged or supported in. To help with this, and to really get to the root of the problems and areas of self-doubt, you need a framework to scope a conversation. The framework I use is the ‘I request — I offer’ framework. This framework can be used in any relationship to remove assumptions and provide clarity.

The below example highlights one I have used for describing a manager-worker relationship, where the worker is defining the boundaries for the relationship with their manager. In this case the worker has made a set of requests of their supervisor, and identified what they offer to this relationship. You can see from the list that the worker values honesty, timeliness, clarity, self-care, and growth. The manager would also have completed an “I request — I offer” for the relationship.

The true value of this step arises in the dialogue that happens after both parties have shared their requests and offers. If there is a separation in what is offered and requested, an honest and candid conversation can resolve the significance of this difference and how to provide a workable solution for both parties.

As an example from my past, I provided information to a meeting that started at 8 am every Monday. The meeting organiser needed the information to work through his agenda which resulted in deciding on a few key activities to be completed during the week. The problem for me was that the system I relied on to get the information didn’t update from the previous week till 8 am on Monday. As such, for the first four weeks of this meeting, I was always about 10 minutes late to the meeting, with the latest information. My colleague grew increasingly furious with me. I couldn’t work out why—the latest information was important to making accurate decisions, and they knew that the system didn’t update till 8 am.

It wasn’t until we sat down and had a conversation guided by this tool that I realised something I did not understand. They prioritised timeliness. When I was untimely, I displayed disrespect for their meeting and disrupted the flow by entering late. I discussed that for me, the most accurate data was the most important, and they countered that in their experience, Friday’s information was current enough for this meeting 70% of the time. I argued that my reviews each morning highlighted enough changes for the new information to be worthwhile. I was prioritising the accuracy of the information.

Through the guidance of this method, we ended up working out that the meeting could actually be held at 8:30 am and we could both be happy. A compromise that meant I was never late to the meeting again and priorities were set off the most relevant information.

Using this framework for all of my mentees has helped me identify that they generally want the same things: honest constructive feedback, personal perspectives and things to learn from (not just what went well), genuine care for them as a person, and to challenge them for growth. Not so different from that of a good leader.

Step 2: Values

Most organisations encourage being values-based. Many of them will have you recite them and pin them on every wall. These are more prominent in some organisations than others, but they are provided as a guideline on expectations, a framework for decision making, and a method for establishing the minimum standards for employees and the organisation.

What I have found interesting is that there is often no work put into the employees’ personal values. Companies expect that by promoting the company values, personnel will suddenly only have those values as their own. Certainly, they should recruit personnel for which the company values resonate, but expecting them to drop their own personal values is not only simplistic, it is disingenuous to them as humans. So how do you work with them on their values?

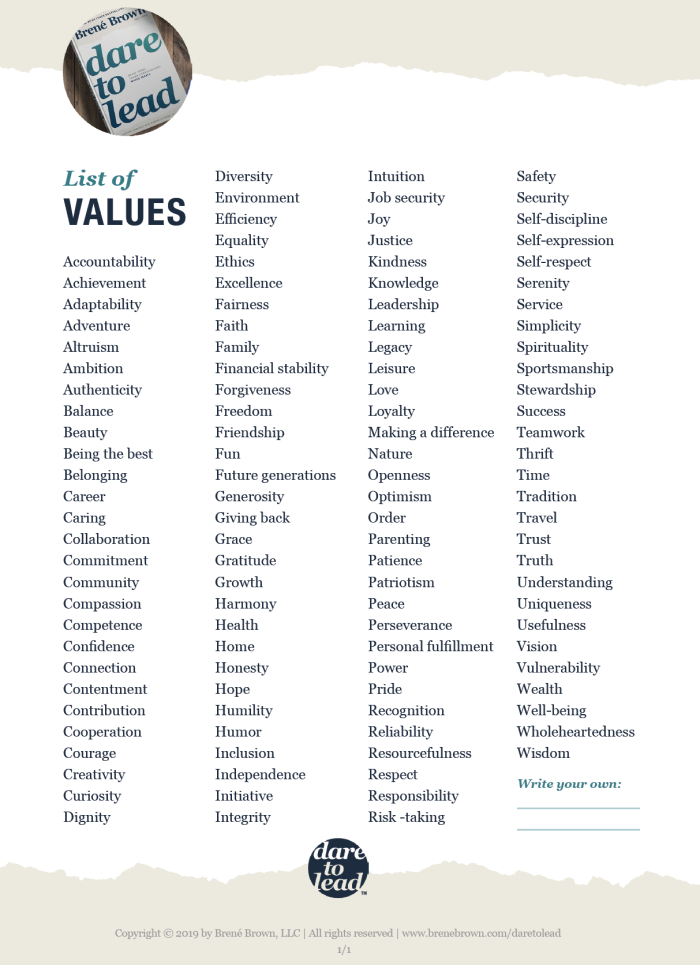

First you have to find out what they are. It is common for people to have never considered their own personal values, let alone had a conversation about them. I certainly hadn’t till recently. One of the most influential things I have read in recent times is the section of Brené Brown’s book Dare to Lead on leaning into your values.

I was struggling with who I was, and what really drives me. I used the process highlighted in her book of using the selected words (in the below figure) to drill down into my own personal values, then I worked out how to lean into them. This has been life-altering for me. The image I use is one of a bucket. What activities, environments, interactions fill my personal value buckets? Doing this blog leans into one of them.

When I do this activity with my mentees, I challenge them to find their two primary values. They’ll often have to whittle it down from an initial ten or fifteen. Once they do, I get them to write their own definition for their two. You need to encourage them to find their current personal values (they will change a little over time), not their aspirational values. Some people will say discipline is a core value, but in reality they aspire to be more disciplined. That is okay, you can work on that with them, but you need to know their core values. It is also common for those with children to say “Family” is a core value. Often it is not—it is definitely important and central to them, but not often a value. Sometimes it is connection, or love, or legacy, or some other underpinning value that manifests in their family.

Next, they need to prepare their definitions for the values. The definition is important, as the word means something intrinsically personal to them. These definitions are often not the ones that immediately come to my mind, and they are important to identifying how to fill their buckets.

For instance, the value of freedom evinces an image of a camper van, sleeping bag, and open fire to me. But to a different person it means freedom from criticism.

Similarly for me, I thought one of my core values was efficiency. When I started to write the definition, I realised that efficiency was just one attribute of my value and in reality the value was growth.

Growth, to me, means being a better version tomorrow than today, and I apply it to myself, those I can influence, and the processes and products I interact with.

My definition of growth includes becoming more efficient, more effective, more purposeful, more collaborative, and more focused. Restricting it to simply a value of efficiency is too narrow for me.

If you and your mentor both understand your values and your definitions for them, your relationship can use this as a platform for shaping your interactions and guiding key decisions.

The last step is to ask your mentee to describe things that add to their bucket, whether it be interactions, events, small things, big things, or environments they feel put something into their bucket. A conversation should then be had to identify how you can put more into those buckets more often. You are in charge of everything that happens inside your skin and you can influence the environment around you.

A good mentor leaves their mentee’s feeling energised and prioritised. Knowing how to shape your interactions to suit their values will help you succeed.

Step 3: Success

The final step to establishing the best mentor/mentee relationship is to be clear about what really matters. You do not need to focus on the issue right in front of them straight away—you need to work out what it is they see just out of their reach. You need to know what success looks like for them.

You need to encourage them to work out what is most important for them and define what their most important goals are. Then they will need to be creative. They will need to turn this goal statement into a set of feelings and transitions in a narrative that is personalised for them.

Below is an example I used to demonstrate how to visualise a future success. This was an example I gave at a “Fear of Public Speaking” group I conducted a six-week workshop series with:

… I knew I was going to give a good presentation when I had my breakfast and a sense of true preparedness washed over me. The time I spent with my presentation coach the day before crystallised the message I was focusing on communicating. When I walked down the hall to the presentation room, I had that little excited flutter in my chest, but I was smiling because I was confident in the importance of my message and the receptiveness of the audience. My slide pack was loaded by the team and whilst there were a fair few people there, the room didn’t feel too crowded. I knew that I had their attention with the opening page of the slide pack due to the catchy title and so I opened with a story as to why I had chosen that story. I could sense the rapport and quickly worked through the topic, focusing on the key takeaways I needed the audience to have. Letting them know there were only a few things they needed to remember kept them engaged. My breathing allowed me to remain calm, and I know that I worked through my vocal range well because I could sense the shifting emotions of the group. As I was drawing to a close, I re-enforced the two key points with a story on how these things impacted them, re-enforced by the facts my presentation had illustrated. I chose not to have a questions slide but to finish on a key point page. As that slide came up, I got a flushing sense of achievement. I knew that they had received my message. I felt great at the end of that presentation. Such a buzz…

This example focuses on how I was going to feel, how I would handle the preparation, and how transitions (from arriving to presenting, from presenting to finishing) would be acknowledged. The same key characteristics are important in solidifying a vision of success for your mentee (and maybe yourself).

So, ask them to identify what is really important, then start to detail what it looks like to get there. They could write it as an award acceptance speech, an end of term feedback report, or a specific commendation narrative.

If they do this, they will begin to acknowledge some of the adversities they will have to overcome to achieve it. This becomes vitally important as a mentor, because it will force them to elicit some of their limiting beliefs or perceived constraints. They will self-identify the areas in which they believe they need the most help.

The Best Mentor Is the One Who Knows How to Challenge People

You’re now set as a mentor; you know what they expect of the relationship, you know where their energy is derived from, and you know where they want to go and what they think they need to overcome to get there.

Doing these three things provides you with everything you need to truly understand your mentee and to know how you are best placed to help them.

- Define the boundaries of the relationship

- Understand their personal values

- Define what success means to them

I will note in closing that these three steps are valid to any relationship. This could pertain to your life-partner—nothing shows love like supporting them reaching their biggest goals and them supporting you. It could relate to family or your teammates on the sporting field. While this type of conversation may seem a little unnatural, it is very beneficial if you’re brave enough to have it.

Good luck!